Background

3-year-old girl is brought to the emergency department (ED) by her parents with a fever and refusal to walk secondary to pain in her right leg. The pain is associated with thigh and back pain on the same side as the limp. The day before presentation, the child's mother picked her up from her babysitter, where she noticed that the child was irritable and crying. At that time, the child was pointing at and trying to touch her back, and she was walking with a noticeable limp. The parents called the patient's pediatrician, who recommended an antipyretic with follow-up the next day. The review of symptoms is only remarkable for a 1-week history of a "cold" with a runny nose and a cough. The mother denies any history of trauma to the affected extremity, and there is no prior history of similar problems. The patient's past medical history is unremarkable. The child is well-appearing and has been regularly observed by the outpatient pediatric department. The patient's immunization schedule is up to date. The child's developmental milestones are appropriate for her age. The family history is noncontributory.

On physical examination, the patient's vital signs are stable, with a blood pressure of 103/66 mm Hg, pulse rate of 115 bpm, respiratory rate of 24 breaths/min, and an oxygen saturation of 100% while breathing room air. Her temperature is 97.5°F (36.4°C).The patient initially refuses to bear weight on the right leg and is unwilling to walk. She is tearful and uncooperative as a result of the pain. The respiratory and cardiac portions of the physical examination are normal. The abdominal examination is also normal, with no palpable masses or tenderness to deep palpation. There is localized exquisite tenderness over the L1-2 region of the back, with slight induration noted in the overlying tissue. The lower extremities are well-perfused, with intact peripheral pulses; no external evidence of trauma is found. There is no limitation in the range of motion at the hip and knee joints bilaterally, with unremarkable obturator and psoas signs. The neurologic examination is normal. No lymphadenopathy is detected.

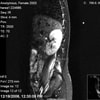

The initial laboratory investigations reveal an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count of 20.5 × 103/μL (20.5 × 109/L; neutrophils, 66.5% [0.66]; lymphocytes, 21% [0.21]; monocytes, 11.3% [0.11]), an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 87 mm/h, a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 49.5 mg/L, a creatine kinase of 69 units/L (69 U/L), and a lactate dehydrogenase of 247 units/L (247 U/L). The urinalysis is normal, with no evidence of infection or hematuria. Plain radiographs of the lumbar spine are obtained (see Figures 1 and 2) and are essentially unremarkable. Since there is a high suspicion for serious pathology based on the clinical presentation and the results of the laboratory investigations, urgent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the spine are also obtained (see Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 1. (Click to enlarge) |  Figure 2. (Click to enlarge) |

Figure 3. (Click to enlarge) |  Figure 4. (Click to enlarge) |

What diagnosis do the findings on the MRI scan suggest?

Please try to answer first before you scroll down

Hint: Look closely at the area of the psoas muscle.

Answer

| Your Colleagues Responded: | |||

| Psoas abscess | Correct Answer | ||

| Spinal epidural abscess | |||

| Retroperitoneal schwannoma | |||

| Retroperitoneal hematoma |

Discussion

As previously mentioned, the lumbosacral plain films were essentially unrevealing (see Figures 1 and 2). The MRI scan of the lumbosacral region, however, revealed a right multiloculated psoas abscess, with paraspinal extension in the region of L3-4 (see Figures 3 and 4) and possible involvement of the ipsilateral pedicle of L3 (not shown in the images provided). Osteomyelitis could not be ruled out based on the images. The abscess measured 1.1×0.6×2.5 cm.

A psoas abscess may be classified as primary or secondary, depending on the presence or absence of an underlying cause. In cases of primary psoas abscess, there is no identifiable source of infection. The psoas muscle is a single structure ("psoas major") in 70% of people, but the remaining 30% also have a smaller "psoas minor", which lies anterior to the psoas major and along the same course. In the lower half of the psoas muscle's course, it runs alongside the iliacus muscle, with a common tendon insertion into the lesser trochanter. Together, they are referred to as the iliopsoas. It lies in close proximity to many organs, such as the sigmoid colon, jejunum, appendix, ureters, aorta, renal pelvis, pancreas, iliac lymph nodes, and the spine. Infections in these organs can contiguously spread to the psoas muscle. A rich vascular supply is believed to predispose it to hematogenous spread from sites of occult infection.[2,3,5,7]

A psoas abscess in children classically presents as a triad of fever, limp, and hip pain. It is important to differentiate between primary disease of the hip and a psoas abscess, as close proximity of a psoas abscess to the hip capsule can result in a similar presentation. This contributes to its extreme clinical variability. Passive rotation of the hip joint in flexion is possible in cases of psoas abscess, whereas in primary disease of the hip, resistance would be likely. Dysfunction of this joint, however, is extremely variable, ranging from complete pseudoparalysis to normal range of motion. In our case, the child presented with the additional finding of tenderness localized to the lower back, which led to an initial incorrect working diagnosis of diskitis. The differential diagnoses in this patient included psoas abscess, pyelonephritis (ruled out by the urine analysis), osteomyelitis, and a neoplastic process. Garner et al has suggested that the incidence of psoas abscess is probably underreported.[11] Primary psoas abscess has a better prognosis than secondary psoas abscess, with a mortality rate of 2.4% (18.9% for secondary abscesses). The median time of diagnosis is 3 days, and the median hospital stay is 27 days. The major cause of death is delayed or inadequate therapy.[6,13,14]

The appropriate imaging studies are important to accurately diagnose this uncommon clinical presentation. Ultrasonography has been recognized as the quickest and least expensive diagnostic imaging modality, as well as being a safe one. It can also differentiate between solids and liquids but, unfortunately, has a low sensitivity. Plain films of the abdomen may show enlargement or loss of definition of the psoas muscle or gas shadows in the soft tissue. Even though findings on plain films correlate poorly with a lesion, especially given the frequent presence of overlying bowel and stool, studies have shown that plain films should be performed before other imaging modalities in patients with suspected psoas abscesses (but may not be necessary if a computed tomography [CT] scan is already planned). CT scans done with intravenous (IV) contrast will show rim-enhancing hypodense areas, with secondary findings of inflammation obliterating surrounding tissue, gas bubbles, and bone destruction when present. There may be marked wall thickening, rim thickening, or multiple cavities, which suggest tuberculous rather than pyogenic infection. CT scans are also useful in recognizing potential etiologies such as Crohn disease and appendicitis. MRI (which was the diagnostic study in this case) has been reported to be more sensitive than CT scanning in displaying tissue contrast resolution and in screening out bone interference, as well as showing the extent of disease. A study by Yin et al recommended the use of a bone scan, especially in patients presenting with low back pain and an established fever of unknown origin, as it allows detection of unexpected concomitant infections.[1,2,3,4,10]

A review of the literature published from 1881 through 1990 revealed that the incidence of psoas abscesses approximates 4 cases per 100,000 population per year, with a more recent Taiwanese study reporting that the rate of occurrence was 2.5 cases annually.[4] These incidences reflect adult patients. In Asia and Africa, 99.5% of all psoas abscesses are primary, compared with 61% in the United States and Canada and 18.7% in Europe. The causes of psoas abscess in the Western world have changed since the beginning of the 20th century. Primary psoas abscesses caused by hematogenous spread from an occult source is common, especially in immunocompromised individuals.

In the past, psoas abscess was mainly caused by tuberculosis of the spine (Pott disease), but with the decline in the prevalence of infections caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, major pathogens associated with psoas abscesses are those related to diseases of the digestive tract. This is reflective of the role of contiguous sites of infection in the development of a psoas abscess. Common secondary causes of psoas abscess include Crohn disease (60%), appendicitis (16%), ulcerative colitis, diverticulitis, colon cancer (11%), and vertebral osteomyelitis (10%). In secondary psoas abscesses, cultures are often mixed with Escherichia coli and BacteriodesStaphylococcus aureus is the most common isolated organism in primary disease. Leukocytosis is the most common laboratory finding.[2,3,7,9] species predominating.

Without localizing tenderness, the presentation of fever and irritable hip could be attributed to primary diseases of the hip and, therefore, it is important that the clinician know how to distinguish between psoas abscesses and primary hip diseases. In psoas abscess, the posterior part of the hip joint is not tender, and a fully flexed hip can be rotated without pain; this would be difficult in patients with hip problems. Digital rectal examinations produce tenderness in psoas muscle disease.

Percutaneous drainage and antibiotics are the first line of treatment, but there is a high recurrence rate. In the past, open drainage of the abscess through a McBurney or iliac crest incision was performed. Open surgical drainage allows simultaneous treatment of the underlying pathology in secondary abscess. The duration of antibiotic therapy must be individualized and graded by the clinical signs and any involvement of other sites.[2,6,8,11,13]

The patient in this case was started on empiric intravenous antibiotic therapy, initially on ceftriaxone 75mg/kg/day. An ultrasonogram obtained shortly after admission was read as a "negative study of the upper abdomen, perirenal and perivertebral lower thoracic lumbar area". Following consultation with the infectious disease service, the antibiotic regimen was changed to cefepime to provide better broad-spectrum coverage. A review of the MRI findings with the interventional radiology department led to the decision that an invasive drainage procedure for a relatively small collection would not be immediately warranted, and a "wait-and-see" approach to determine the response to the intravenous antibiotics would be the best course of action. After 3 days of intravenous antibiotic therapy, the child's fever subsided, and she was noted to be moving around without limping and with no residual tenderness on examination. If fact, her mother described her as "back to her old self." A consultation with the neurology service found no neurologic deficits, and the initial limp was attributed to pain. A repeat CRP level was obtained, with a result of 34.5mg/L. The final results of the blood and urine cultures, as well as a purified protein derivative (PPD), were all negative.

As the child was doing well clinically (running and jumping up and down) and had a compliant parent, the patient was discharged on hospital day 5 with a combination antibiotic regimen of rifampin and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid for 4 weeks, along with appropriate outpatient follow-up with her primary pediatrician and an infectious disease specialist. Repeat MRI scans performed at 1 month and again at 3 months after discharge demonstrated complete resolution of the collections, except for a residual "abnormal signal intensity in the right pedicle of L3", which persisted with no identifiable clinical impact; the patient was noted to have complete resolution of her symptoms. It should be noted that the use of IV antibiotics as the sole modality of therapy in our case was unusual for the management of a psoas abscesses.

Questions

Which of the following statements about the psoas muscle's anatomy is true?

Please try to answer first before you scroll down

Answer

Which of the following statements about psoas abscess imaging is true?

| Your Colleagues Responded: | |||

| MRI has been reported to be more sensitive than CT scanning | Correct Answer | ||

| Ultrasonography is more sensitive than CT | |||

| A negative plain film of the area can rule out psoas abscess | |||

| CT scanning is the least expensive and quickest imaging modality |

Which of the following statements about the psoas muscle's anatomy is true?

| Your Colleagues Responded: | |||

| The psoas muscle together with the iliacus muscle is referred to as the iliopsoas. | Correct Answer | ||

| Seventy percent of individuals have a smaller secondary psoas muscle. | |||

| The psoas muscle is relatively isolated from other organs. | |||

| A poor vascular supply can cause hematogenous spread from sites of occult infection. |

- The psoas muscle is a single structure ("psoas major") in 70% of people, but the remaining 30% also have a smaller "psoas minor", which lies anterior to the psoas major and along the same course. In the lower half of the psoas minor's course, it runs alongside the iliacus muscle, with a common tendon insertion into the lesser trochanter. Together, they are referred to as the iliopsoas. It lies in close proximity to many organs, such as the sigmoid colon, jejunum, appendix, ureters, aorta, renal pelvis, pancreas, iliac lymph nodes, and the spine. Infections in these organs can contiguously spread to the psoas muscle. A rich vascular supply is believed to predispose it to hematogenous spread from sites of occult infection.

| Source: http://cme.medscape.com | |||

No comments:

Post a Comment